See What I See

SPC grantee uses the power of the pen and lens to highlight West Siders perspectives so they can tell their own stories.

Richard Marion was just a youngster — 6th or 7th grade, he can’t recall — when he discovered The Westside Writing Project (WWP).

“We used to go to Chicago Commons, going up there just after school, getting on computers, wasting time after school,” he says. There he and his friends met Frank Latin, WWP executive director, who offered them a little cash to produce stories for a neighborhood newsletter.

Since then, Marion’s learned “pretty much everything” about video production, and media is the career path that the now young man has fixated on. “It was just, ‘we put the tools in your hand and then you go make it happen,'” he says.

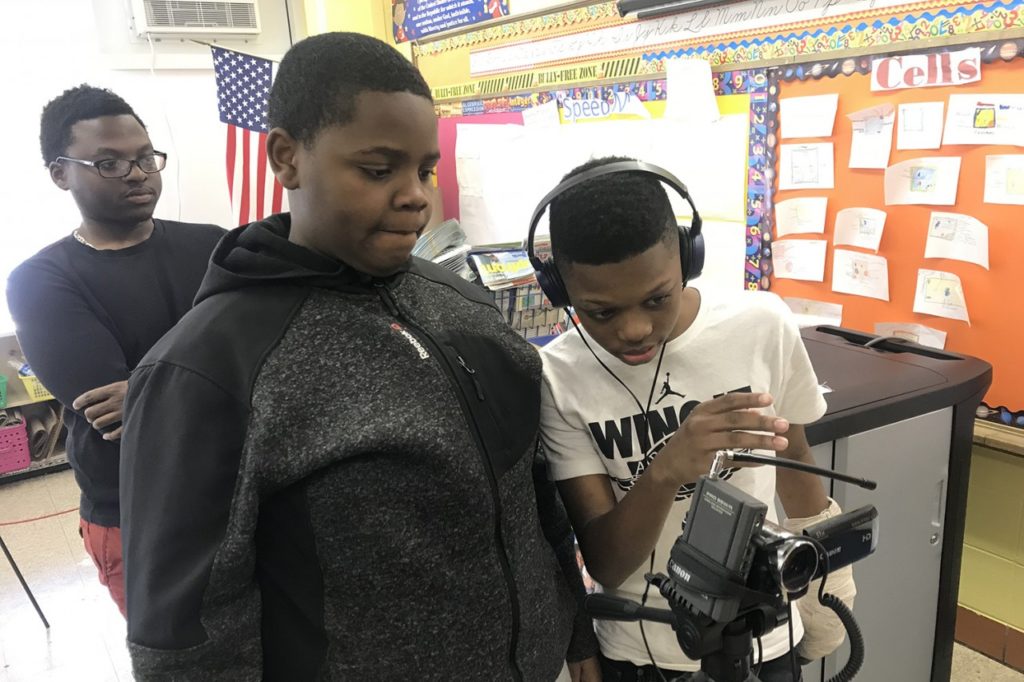

This is WWP’s precise aim. Latin describes the organization as a community media outfit meant to engage both local residents and youth. “At the heart of Westside Media is storytelling, and we provide the tools and resources for our students and community members to tell their own stories,” he said. “We have students working behind the camera, crafting their own story.”

Over the summer, Westside Writing Project fellows filmed various interviews where individuals discussed violence in the community; those works became two projects that the organization screened in October — “Summer of Life,” which was filmed over the course of about four weeks, and “16 Shots and a Cover-Up,” a look at the West Side as the city prepared for the verdict in the Jason Van Dyke trial.

“Community members came together talking about the impacts of violence and solutions to violence,” Latin says. “It fits our narrative because community members were coming together to discuss and create solutions to our own problems, as opposed to someone from downtown coming in and trying to tell our story.”

“We know what’s going on in our community and we’re trying to shed a better light on the coverage,” Latin emphasizes.

Cedric Frison, born and raised on the West Side, had seen parts of the documentary beforehand, but seeing the completed project was a much different experience.

“It was powerful: different approaches to solutions, different perspectives on what causes the violence. Hearing all these different residents, who live it and who see it every day, breaking it down,” he says.

For Frison, life on the West Side hadn’t been pretty. “I got a lot ‘ex-s’ on my name,” he says, noting himself to be an ex-drug dealer, ex-drug addict, ex-gang member and ex-college drop out who is now a changed man: a recovery and outreach specialist, community activist and Northeastern University student pursuing inner-city studies. He sees stark differences between what things were like when he was growing up and how things operate for kids today — through his activism and work with READI, he is always thinking about ways to lure young men away from street life, and he says WWP offers a fresh spin and new route.

“The culture has shifted; one thing about the gang culture in Chicago is that it had some structure [but] I’m not justifying anything…there’s stuff our youth is doing now that wouldn’t be tolerated [then],” he said. “[Storytelling] is something that’s needed, and it’s going to bring awareness because a lot of people don’t know…we get so locked in our situation that we’re dealing with, and it’s hard to see what’s going on outside of that.”

“A lot of people don’t want to deal with it, [they want to] recoil and isolate,” Frison says,

The real world implications of the work — refusing to let people recoil, ignore or be voluntarily or involuntarily isolated — is what has kept Marion coming back to WWP for a decade now, returning from Iowa State University just in time to edit the entire “Summer of Life” project.

“I was used to hearing people come in and tell these raw stories, telling stories you hear every day, you hear in passing, you hear growing up. But now you’re seeing it, seeing it in a different setting; you see all this emotion pouring out of people,” Marion stresses.

“The stories here are the stories they don’t talk about on the news. It’s the stories that a lot of people know, that’s why there’s a lot of familiarity from the people watching the videos: They relate to it because it’s the stuff they hear,” he says. “I learned that the same things have been going on [over time]…it’s basically the same things happening so it gives you some kind of perspective that a lot of this stuff is just repeating.”

While there’s an allure to grab that big media job downtown after college, Marion is lured back to his neighborhood to break up some of that monotony. “You’re able to tell [stories] from your own perspective and you’re able to make change: other organizations, they’re doing it for business purposes.”